Pages

Monday, October 31, 2011

Eiko Ishioka Featurette for Tarsem's "IMMORTALS"

Friday, September 30, 2011

"VERTIGO" Envisioned: Storyboards from Alfred Hitchcock's Masterpiece

Monday, August 22, 2011

Sequential Art Primer Part 3: The Three Modern Masters and the Essential Transcontinental Chain Reaction

Jean Giraud/Moebius

Hayao Miyazaki

All three artists contributed to their regional form of ‘sequential art.’ More importantly, their work is linked together in a ‘chain reaction’ of influence that led them to create work in a very similar stylistic language that marks a significant evolution of ‘sequential arts’ aesthetic as a global form. Starting with Rober Crumb’s work in ‘comics’ in the ‘60s, continuing with the 'bande-dessineé' work of Jean Giraud/Moebius’ in the ‘70s, and ending with the 'manga' work of Hayao Miyazaki in the ‘80s.

R. Crumb’s gift as an artist is a quality that many would consider a flaw. Crumb seemed to lack any ability to filter himself in his work. The other gift that Crumb possesses is an inability to stop. As an artist, R. Crumb’s significance was not the result of an objective to become important or to create work that was original or independent, but rather an incredible capacity to bear his soul and be authentic. With such work in “Comics” like “Zap Comix” his cross-contour drawing style and perspective as and artist is evocative, offensive, neurotic, and revealing. He was provocative without being a deliberate “provocateur.”

While I consider George Herriman to be the true innovator of some of Crumb’s linguistics, in the 1960’s, Crumb’s evolution of his cross contour style combined with his boldness of subject makes him an essential figure in the evolution of “Comics,” and “sequential art.’

R. Crumb’s influence can e seen in the evolution of Jean Giraud’s alter ego “Moebius” and his ‘bande desinée’ work of the 1970’s where he expresses aspects of his inner psychology across the surreal fantasy landscape of “Arzach” in an echo of the Crumb style and with a clear sense of newfound liberation. After Crumb, what ideas should sequential art fear expressing? What need is there to strive for perfection in one’s draftsmanship once such a skill becomes as easy for the artist as switching on a light?

Moebius’ “Arzach” uses a fantasy landscape to express the personal in metaphor. The landscape and inhabitants of “Arzach” create an eerily cohesive world, no matter how bizarre, as a direct result of being manifestations of the many facets of Moebius’ psyche that he now feels emboldened to express. The hatching on the hand-lettering, the wonky panel borders and use of circular frames show a new sense of freedom applied to a dreamscape that are echoes of Crumb.

Moebius’ use of metaphor offers accessibility to the audience that Crumb’s more raw and personal explorations deny. Metaphor translates the personal to the universal and allows the audience to access the work on two levels of depth. “Arzach’s” aesthetic is the precursor to Hayao Miyazaki’s move away from the stylistics of Osamu Tezuka, and toward the freeing and more primal cross contour mark-making of Crumb and Moebius with his 1980’s ‘manga’ work “Nausicaä.” Elements of “Arzach” and “Nausicaä” share many similarities in much the same way that “Arzach” shares similarities with R. Crumbs pioneering “Zap Comix.”

The quality that seems to be driving Hayao Miyazaki’s work forward at this point is the contagious feeling of liberation that comes from giving one’s self permission to draw without the concern for your work being free of imperfections and rawness. In “Nausicaä,” Miyazaki’s desire to reconnect with mythology and the natural landscape within the context of a society increasingly seduced by the allure of technology is depicted in a fantasy world that assimilates both.

Familiar elements of architectural style, means of flight, and otherworldly cultures and creatures that appear in “Arzach” can be seen in “Nausicaä” and, more significantly, its illustration technique owes much more to the tradition of 'bande dessinée' than those traditionally associated with 'manga.'

Friday, June 17, 2011

Sensei, My Sensei: Kurosawa's "Throne of Blood"

Monday, May 30, 2011

Dean DeBlois and Chris Sanders: Exploring the Future and Challenging the Past (Part 1)

Update:

Tuesday, May 24, 2011

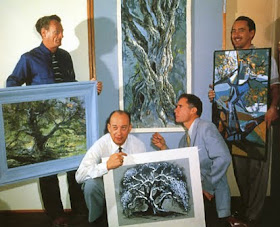

4 Artists Paint 1 Tree: A Walt Disney 'Adventure in Art'

Saturday, April 23, 2011

Sequential Art Primer Part 2: The Second "Tongue" of "Sequential Art" and the Essential Iconoclast

“Sequential art” is a form of visual communication that has three distinct pillars and after discussing comics, bandes dessinées, and manga as well as the masters of those pillars, any serious student of "sequential art" should continue their study beyond these three regional inflections with the artist I like to refer to as “The Iconoclast of Sequential Art,” George Herriman.

Words fall short when describing the enigmatic artist who burst forth from the region of America that also contributed to the richness of the country’s musical landscape with Jazz. George Herriman, the creator of the classic comic work “KrazyKat,” possessed many of the attributes that would have allowed him to be successful creating conservative work that used the existing conventions of the form.

George Herriman, however, had other plans. Herriman, who possessed a fertile and free mind, much like those musicians whose explorations led to the birth of Jazz, became the preeminent force behind the linguistic innovation we call "cartooning."

Tuesday, February 15, 2011

Sequential Art Primer Part 1: The Three Pillars of 'Sequential Art' and the Essential Masters

Most of the theories, for the decrease in the size of the audience tend to overemphasize the obstacles the form faces when competing against more modern forms of storytelling and neglect the fact that the 'sequential art' storyteller has never, in the history of mankind, had a more direct line to the audience of the world. The task of showcasing one's work, promoting it, and making it available for order directly to the public has never been easier. In addition, ‘sequential art's’ unique ability to go anywhere and say anything has only been hindered in the past by a combination of manufacturing cost, regulation, and distribution monopolies that are eroding before our very eyes.

It may be that it has been far too long since the audience in the United States has been reminded of the vitality ‘sequential art’ is capable of. It is equally possible that the young creators of today's 'sequential art' have been divorced from the form's history, which is as rich as any other form of art. By studying this history, these creators may find inspiration in the work of a kindred spirit not only from another country but from another era as well.

The aim of this post is to offer a starting point for future storytellers and makers of 'sequential art' to begin their exploration.

There are three forms of modern ‘sequential art’ that constitute its pillars: ‘comics’, ‘manga’, and ‘bande dessinée’. These three forms are the most significant stylistic variations in ‘sequential art,’ and have evolved as the result of diverging regional tastes, innovation, and distinct cultural perspectives.

Storytellers of the modern era have been cross pollinating these approaches for many years now, and while that is encouraging in what it affirms about global society, it has also led to stylistic artifacts being adopted and used with little or no understanding of where they originated. The ‘comic’ has been greatly diminished by its inability to meet the needs of the modern audience and reconnect with its rich history and let go conventions that are the artifacts of a bygone zeitgeist.

Below is an introduction to artists whom I would offer as the most essential to study from each of the three pillars of 'sequential art.'

‘Comics’ is the name of the art form that was established in the United States with the ‘comic strip,’ and popularized the combining of the word balloon with sequential pictures in the early 20th century. ‘Comics’ began in newspapers and these ‘comic strips’ were eventually collected in ‘comic books.’ By the 1930’s, ‘comic books’ of original material began to appear. Eventually these books were published in albums called ‘graphic novels,’ and just as with ‘comic books,’ original graphic novels of long format stories are now created. Modern day sequential art produced in the United States lacks diversity of subject matter and is geared toward a small audience that is more a ‘subculture’ than ‘culture’ as a whole. Most of the prominent characters that were created in ‘comics’ are not closely associated in the public’s mind with the creators who created them, with the exception of a handful of ‘comic strip’ characters.

While it is difficult to hold up any one artist as being the most essential to study in a given art form, I would offer Winsor McCay as the first true master of modern ‘sequential art’ and ‘comics.’ Winsor McCay made his name using an entire page of a newspaper as his canvas and creating “Little Nemo in Slumberland” in the early 1900’s. With these weekly full-color installments, he created the first major benchmark to measure all future works against. After a century, his imagination, craftsmanship, and innovative storytelling devices make him essential reading in the study of ‘comics.’

In ‘bande dessinée,’ Belgium’s Georges Remi, known by his pen name Hergé, created a body of work that still resonates today in the form of his 24 volumes of “Les Adventures de Tintin.” Hergé was similar in the way he spoke to the audience of his day by evolving his art’s visual clarity and creating a style that became known as ‘ligne claire’ (clean line), while doing meticulous research of locations to transport the audience.

Below is the elegant title image from “Tintin au Tibet” which showcases the production value and craftsmanship seen in ‘bande dessinée,’ as well as one of the most memorable pages in the entire series of “Les Adventures de Tintin” from the same volume.

Manga’s most important artist is by far the easiest to proclaim, because he stands utterly undisputed. Osamu Tezuka, created a cast of characters and body of work that rivals the entire catalogue of corporate institutions in the United States that have spent decades acquiring characters and works from hundreds of artists. Tezuka innovated a style, a visual language, and produced more ‘sequential art’ than Winsor McCay and Hergé combined.

Sunday, February 6, 2011

Guillermo del Toro's Pan's Labrynth